P-3 Orion Research Group

The Netherlands

this page was last updated on 27 January 2013

Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion Stories

A “Russian” P-3 attacked RAF St. Mawgan

By Erik Kopp, Vice Admiral, RNLN (ret.)

On 26 June 1989 we flew a very special mission to RAF St. Mawgan in Southern England. We were invited by the Royal Air Force to enter the air base’s airspace disguised as a Russian Tupolev Bear D and to land at St. Mawgan as part of a Tactical Evaluation (TacEval). We flew our P-3C Orion #301 to another British air base to pick up an English/Russian interpreter and together with her we flew into St. Mawgan’s aerodrome traffic zone. We called the tower in Russian language and asked permission to land. George Bornheim was our pilot and he was a real dare devil. He made several very low approaches to St. Mawgan, even when the RAF blocked the runway with fire engines. They absolutely did not want us to land there. Finally we landed while calling out Russian swearwords over the tower frequency. Immediately after our roll out, our aircraft was surrounded by fire engines and armed soldiers. With signs in Russian language they tried to make clear to us that we had to follow the “follow me” car, but we decided to stay on the runway. The Brits forced the crew to leave the aircraft, but George and myself stayed onboard while we were waving with real Kalashnikov guns. They could not appreciate this at all and threatened to send two dangerously looking sheep dogs inside the aircraft. After a couple of hours we went outside as well, where we were heavy-handed thrown on the ground and body-searched. Finally the crew went in a bus all together and the exercise was ended. This was a very funny mission to do. A real test for the air base and we could put our own creativity in it. In the afternoon we returned to RNLNAS Valkenburg.

The Gear Pin Story

by Richard A. Hoffman, Captain, USN (Ret)

The events of this little tale were a little embarassing to the crew involved at the time, and they could have been career-ending for me, but fortunately for all involved, VP-8 spirit and humor saved the day. If anything, VP-8's reputation gained in stature because of the way in which our shipmates handled the situation. As you know, VP-8 was the first Atlantic squadron to deploy to the Far East in support of the Viet Nam effort. Our arrival was the occasion for a lot of the Pacific VP Community to question as to whether or not this Atlantic outfit could cut the mustard in the very different Pacific environment. It didn't take long for the question to be answered: VP-8 was a top-notch performer capable of performing any and all assigned missions.

We got along very well with the Fleet Air Wing Commander, Captain Dave Kendrick. In the course of a normal reassignment, Captain Kendrick was relieved by Captain Les Barco. The good news was that Captain Barco had been skipper of an Atlantic squadron, so we were spared the task of reproving ourselves. But Commodore Barco ran a taut ship. He demanded performance and he did not suffer fools lightly. That was fine with VP-8 and our operations continued to run like clockwork. Things were going so well and nothing was on the schedule except a routine, midnight takeoff Market Time mission to be flown by one of my most reliable PPCs, Lieutenant Commander Hal Taylor, so I decided to take a night off and go to Manila for a party at the Army Navy Club. It was a great party and I arrived back at Sangley Point in the wee hours and probably a bit worse for wear. I was just about to settle in my bunk when the XO came in and told me that we had a problem. It seems that the scheduled aircraft launched on time but when it got airborne the PPC could not get the wheels up. Because of airspeed and manuevering limitations , flying the assigned mission with the gear down was impossible and it was necessary to launch the backup "Ready Alert " aircraft. The supposition was that the "gear pins": steel pins which prevented the landing gear from being retracted on the ground had not been removed. There were three of these pins on each aircraft and each was attached to a long red cloth streamer which read "Remove Before Flight".

The uninitiated might think "no problem", all the PPC had to do was land, remove the pins and go about his business. But it wasn't that easy. The patrol had taken off at Maximum Take-Off Gross Weight, which was far heavier than the allowed landing weight. A landing at Maximum Gross Weight was permitted in an emergency, but after such a landing the aircraft had to be grounded until an extensive structural examination was performed. Since our early P3s were not equipped with a fuel dumping system, the PPC could not land until enough fuel was burned off to bring the aircraft down to a permissible landing weight. Therefore the aircraft was orbiting over Sangley Point burning fuel and I was informed the landing-gear-down aircraft planned to land about 0730. The squadron duty personnel had handled the situation in a professional manner and the assigned mission was covered. In fact, Crew THREE, Lt Ed Weiss PPC, had launched within 15 minutes of receiving orders and had arrived on station on time. Since there was nothing more I could do, I turned in.

The next morning I arrived at the mess to find the Commodore in a state of high dungeon.. To say the least, he was not a happy camper! He told me I was to accompany him to the flight line to greet our errant brother-and the inference was that the PPC and I would be the subjects of a world class reaming! I can't say I enjoyed my breakfast. Finally the Commodore gruffly said "come with me" and we drove in silence to the flight line. As we drove along, my mind was occupied with making plans for a new career, since this incident seemed to spell the end of any future that I might have had in the Navy.

When we got to the flight line we were greeted by an amazing sight. The entire squadron was there and each and every man jack was waving a red streamer which said "Remove Before Flight". I didn't know that there were that many red streamers in all of Sangley Point. As poor Hal and Crew 8 taxiied in, they received a royal rassing from the whole squadron. The ramp was covered with VP-8ers yelling and wildly waving red streamers and they formed a gauntlet through which the embarassed crew had to pass as they left the aircraft. (For a long time the PPC stayed in the cockpit with his face covered-I thought I would have to send the Shore Patrol to get him out.) I must admit my first thought that this seemingly frivolous display would make things worse: that Commodore Barco would think VP-8 did not take its responsibilities seriously. The Commodore stood watching the proceedings with a stoney face until all of a sudden he broke into a big grin and said it was the damdest thing he had ever seen. With a big smile he turned to me and said: "You guys know how to handle things" and then he got in his sedan and drove away.

For the rest of the deployment, Commodore Barco was VP-8's biggest fan and he and I became pretty good personal friends. In reviewing this tale with Hal, I found that it was LCDR Wil Roberts who had the bright idea to pass out the gear pins and streamers to the crew. During the night, while Hal was circling over Sangley, Wil got every "Remove Before Flight" streamer in Sangley Point Supply and arranged for an early muster so the whole crew would be on hand. Furthermore, Wil had a forty-foot red "Remove Before Flight" banner made and draped over the squadron Quonset. Hal said that he saw the banner while on final approach and knew he was in for it. Thanks Wil!

Wil continued to stick it to his friend Hal. On the transpac returning from Sangley, Wil preceded Hal and at every field along the way: Guam, Barber's Point and Patuxent, whenever LC-8 asked for landing instructions, the tower asked: "Is this the fixed gear P-3?". There is a little sequel to the story. In 1972 while visiting NAS Moffett , I found outthat Hal, now CO of VP-19, was returning from deployment that very day. I went out to the flight line to join the welcoming committee and while we were waiting for him to taxi in, I "borrowed" a gear pin complete with a "Remove Before Flight" streamer which I rolled up and hid in my right hand. After the official welcome was over and after he hugged Greta and the kids, I went over to offer my congratulations on his successful deployment. As I shook his hand, I slipped him the gear pin. I swear he blushed!

Droop Snoot testbed

By Dick Hoffman (Droop Snoot’s pilot)

This photo, dated 2 November 1964, was of an experiment we did at Patuxent River with BuNo 148889. As you know the P-3 has two radars. We wanted to see if one radar would work as well. The Droop Snoot configuration was picked purely for ecomony and was never meant to be a production design. By building an inexpensive airframe "wedge" between the P-3's fuselage and by making a simple antenna-lowering structure, we were able to use the expensive standard nose radome without modification or damage. The experiment worked well, but the Navy decided to retain the two radar configuration. After our tests, we removed the "wedge" and put the forward radar antenna back on its standard mount, and thus restored the aircraft to standard at very little cost. Flying qualities seemed to be uneffected by this modification. I could not tell the difference in handling from a "standard" P-3. Because we had not done an extensive structural or aerodynamic analysis on the experimental configuration, the Bureau of Aeronautics limited our top speed to 250 knots, so we did not attempt any analysis of the effect of this configuration on performance. We did observe that handbook power-settings yielded close to handbook airspeeds. As I said, it was never meant to be a production design.

Unforgettable P-3F delivery flight

By Vic Ehlers (P-3 Flight Instructor)

On 31 March 1975, the first three P-3Fs departed Moffett Field California for Iran, with crews comprised of Lockheed and Iranian Air Force personnel. We arrived in Bandar Abbas on 10 April after lengthy stops in McGuire AFB, Lajes Field (Azores), RAF Lyneham, Naples and three hours in Tehran for entry customs. Our arrival at the Tehran Mirabad airport was rather exciting. Approximately ten miles out, Col. Houshmand, the squadron's commanding officer, contacted the tower and requested a low flyby to show off the Air Force's newest acquisition. He received clearance for the pass and we approached the airfield in a fairly decent “V" formation with Major Bardshiry, the Executive Officer on the left, and my student and I on the right. The lranians were all flying in the left seat and the Lockheed instructors in the right. Approximately three miles out, and with the command to "follow me", the Colonel went to military power and dove for the deck. This all happened so fast that the two wing men were left far behind trying in vain to catch their leader. Their total concentration was on the Colonel's aircraft in spite of the other traffic in the area. This tended to create a slight bit of anxiety among the Lockheed instructors, especially when the airspeed pointer approached the Vone needle and the RAWS warning went of. With one hand under the yoke and the other resting on the power levers in the best traditions of the flight instructor, I was able to assist the student with a reduction in power and also in arresting our descent. Relief was only momentary, however. The flight path of our "almost formation", put the colonel down the center of the airport while Major Bardshiry's aircraft buzzed the Air Force F-4 ramp. My aircraft was lined up directly with the civil ramp in front of the main passenger terminal. I don't think the passengers walking out to their planes saw us coming, but I suspect they were diving for cover as we passed overhead. After thrilling our unsuspecting audience, things got even better. What began as a dot on the far side of the terminal at our altitude, rapidly became a helicopter that just happened to be hovering directly in our path. This did nothing to lessen my personal anxiety level. I issued my first in-country “I've got it”, yanked back on the yoke, successfully avoiding the little guy, and seized the opportunity to review the instructor / student relationship. I don't know what happened to the helo as we overflew it, but I imagine the pilot's life became very interesting for a few moments. Like us, he won't forget the day the P-3Fs arrived in Tehran.

One tough birdie - a bumpy WP-3D ride into hurricane Hugo

as published in Lockheed’s “Airborne Log” of May 1990

14 September 1988, Barbados, West Indies. NOAA WP-3D aircraft N42RF and N43RF departed home base at Miami International and set course for Grantly Adams International on the island of Barbados to establish an operational base. At their evening arrival they were met by a local reporter, The Nation Newspaper's Janice Griffith, who had been approved to ride along and wanted to confirm her seat on the first flight into Hugo.

15 September 1988, Grantly Adams International. Just before noon, Janice arrived at the airport and met Program Coordinator Dr. James McFadden. Dr. McFadden spent some time trying to explain what Janice was getting into. Janice wasn't fazed. Hugo was about an hour east. Two NOAA P-3s Would work the storm together; an Air Force WC-130 would also be working, but higher. N42RF with Janice aboard would enter the eye at 1500'. N43RF would work the perimeter at 20,000'. Flight crew was typical for a hurricane hunt: Pilot Gerry McKim, Co-Pilot Lowell Genzlinger, Flight Director Jeff Masters, NAV Sean White, Flight Engineer Steve Wade. The tactical crew consisted of Hurricane Program Manager Dr. James McFadden, Meteorologists Drs. Pete Black, Bob Burpee, Frank Marks, Hugh Willoughby and Peter Dodge. Terry Schrickner and Alan Goldstein served as electronics engineers while Neil Rain was the electronics technician. On the radio was Tom Nunn.

14.6 degrees north, 54.6 degrees west. NOAA 42 was at 1500' anticipating entry into the eye of Hugo. Janice had strapped in securely and the plane was as ready as ever. This would be copilot Lowell Genzlinger's 249th eye penetration. Janice was taking notes as well as possible in the constant buffeting; she observed the WP-3D was in its 14th year and the time was 1:28 p.m. As the plane was about to enter the eye, the sky grew dark and Janice set aside her pen. Later she filled in with the following, "All hell seemed to break loose around me. Briefcases, cups, soda cans, books, anything unsecured came clattering down. I just gripped the nearest arm and held on for dear life." Though not familiar with the norm, Janice had properly recognized an aircraft out of control. According to Pilot Gerry McKim, the plane was doing what it wanted. Nothing they did changed anything. Full aileron one way and the plane went the other. For an eternal two min utes, their fate was unknown. The beating they were taking was as bad as anything the team had ever experienced. A crash in the cabin was the sound of a life raft breaking loose and nearly puncturing the ceiling. The rain pounding against the fuselage was deafening. The instruments were unreadable. Both pilots fought back with all their might.

Number three engine at this point overheated to 1260 degrees, torched and was shutdown. Suddenly the sky cleared to the right. The pilots forced the plane toward the clearing, starboard into the bad engine. The aircraft lurched and dropped 800 feet in 20 seconds. Desperately, the flight crew started dumping fuel and expendables as fast as they could to halt the descent. The radar attitude was about 700 feet over a boiling ocean of 65 foot waves. The turn into the clear and quick action by the flight crew paid off at last. They had entered the eye and were able to get the aircraft back under control. The diameter was 8 miles -a tight one. Pilots McKim and Genzlinger began a slow climbing turn to regain their lost altitude, while in an eye that offered little reprieve from the turbulence. They had many concerns, but getting out seemed to override the fact that they had to abort the mission; they would not meet their objectives. This sortie's eight planned penetrations at different altitudes would yield no data. But as meteorologist Bob Burpee pointed out, getting the crew back was their first objective.

The Air Force WC-130 was called for assistance. After 17 turns now at 7000' on the radar altimeter, the crew noticed a weak area in the eight mile thick eye wall. The Air Force WC-130 would check it out for them. Soon the P-3 was following the WC-130 through the soft NE side of the wall. N43RF and the WC-130 were checking 42 for visible signs of damage. "There was a real mess in the back," Genzlinger remarked. "All the drawers were out and everything was scattered. The G meter read -3.5 to + 5.6. We'd never seen anything like it and never want to go through that again." Both planes headed back to Barbados. Only N43RF continued flying missions on Hugo.

After defying what may be the worst beating a P-3 bas ever taken, N42RF was cleared for 3-engine ferry back to Florida by an inspection team out of NAS Jacksonville. The airplane was scheduled for SDLM the following months; NOAA decided to send it off early. Maintenance determined that fuel control temperature sensor failure caused the overtemp. Later they found no new cracks that could be attributed to the violent entry into Hugo's eye. A normal SDLM for the aircraft's age and hours was scheduled. The G-meters were checked for accuracy because of the unbelievable readings. The +5.6 was correct. The -3.4 should have read -3.9! The WP-3D is rated for + 2.5 and -1, so the only explanation for the wings remaining intact is the instantaneousness of the blow and the probability that the force occurred far forward in the fuselage. With the P-3's monocoque design, the forward fuselage acts like a giant spring. Also, the aircraft was rarely in a straight and level position during the worst turbulence. Copilot Lowell Ginzlinger's memento of the now famed Hugo flight tells a horrendous story. In a 30 second period, the vertical wind changed from + 45 knots to -20 knots, and flight level winds changed from 190 knots to 50 knots. The aircraft lost 700 feet of altitude, and pressure dropped to the all-time Hugo low of 915 mb; lower than the central eye pressure by 15 mb. The crew had never experienced such a ravaged interior. In retrospect they concluded that strong sideloading during the unprecedented attitudes and G-forces accounted for the difference. The NOAA teams' biggest regret (besides being on the flight) was that N42RF was sent off to SDLM when a simple fuel control change would have made it capable of more flights into Hugo.

Clarke’s Stork Taxi

By Tom Clarke, CDR, USN(Ret)

In 1978, I was deployed to NAS Sigonella, Sicily flying the P-3C aircraft with Patrol Squadron 45, homeported at NAS Jacksonville, FL,. At the time I was the Maintenance Officer and on this particular day, my crew (CAC-9) was serving as the maintenance duty crew. It was a fairly routine day until we received the call from Ops to launch the Ready One for a Medevac (Medical Evacuation) flight to Naples, Italy with a pregnant woman who was having issues. I went up to the Operations Office and suggested that since it was a quick, about 55 minute, flight to Naples that instead of “burning up” a ready alert crew, why not use the maintenance crew? Everyone liked the idea and Crew 9 started to preflight LN-48 for a pleasant afternoon flight to Napoli and return. Little did we know!

The electric shop rigged up a 60 Hz power converter (Unitron) for the incubator in case it was needed while my copilot and I did a quick weather brief and filed for Naples. My FE grabbed me and said, “Hey, Commander, how much gas do you want?” After a microsecond’s thought I answered, “Just up to Naples and back, a ramp load will do it.” Little did we know!

Things were progressing nicely and the ambulance showed up with our “passenger”, Mrs. Brenda Domogauer and her husband, Chief Domogauer. The base dispensary thoughtfully sent along a nurse, LT Lisa Hiles to accompany the patient to Naples. We were beginning to think, “What a nice way to spend a maintenance duty day and bag a little flight time too.” Little did we know!

After Mrs Domogauer was “strapped in” another ambulance showed up! It seems an additional Sigonella “Mom to be” was going into labor and needed to get to Naples. Since Mrs D was on a stretcher tied down next to the P chutes, our new “customer” got one of the bunks. Everything was looking good, so we took off for Naples. Typical Med weather, a little haze, no clouds and smooth all the way. This is Naval Aviation at its best and they pay us to do this! Little did we know!

About half way to Naples, we received a call from Roma Control, informing us that we needed to call our base for a message. Since we were out of UHF range, it was “Croughton, Croughton, this is Navy LN-48 on 89 upper”. We lucked out and got a good HF phone patch and found out that they didn’t want us at Naples that we were to go to Rhein-Main Air Base in Frankfurt Germany. Now this is getting interesting! A couple of thoughts went through my mind, like; Fuel, Flight Plan, Diplomatic Clearance, Swiss Overflight clearance, oh, and by the way how about some chow? I elected to land at Naples and take care of these “admin items.” Little did we know!

The folks at Naval Support Activity at Capodocino Airport in Naples fixed us right up with fuel, weather, flight plans, dip clearance, and yes, even some box lunches. While all this was going on, another ambulance showed up with “another patient for Rhein-Main”! Sure, why not, we have another bunk open, but I am not going anywhere with three pregnant ladies, without a doctor on board. Shortly thereafter Lcdr, (Dr) Soballe climbed aboard. “Ladder’s up, Door secured” was the report from AWCS Avery, our SS-3 and soon to be “honorary midwife,” but I am getting ahead of myself!

Off we go into the setting sun for the trip to Rhein-Main. ASCOMED (Air Surface Coordinating Office-Mediterranean) sometimes irreverently called “FiascoMed”, in Naples told us to take the shortcut across Switzerland, that they would get overflight clearance for us. I thought about that for about a microsecond, and continued up the long way around through France. We flew up the West coast of Italy over Florence and Genoa, then across to Lyon, Dijon and Strasbourg in France, then over Mannheim, Germany and on into Frankfurt. Sometimes you make the right call, and as it turned out, our overflight clearance didn’t come through until we were on the return leg!

As we motored on through the night, our thoughts turned to the upcoming RON in Frankfurt and that little restaurant in the town of Zeppelinheim, just outside the gate at R-M, and the possibility of dining on Wienerschnitzel and some Bavarian beer (scrupulously observing the requirements of 3710.7!). Little did we know!

About an hour or so out of Frankfurt, Doc Soballe came up to the front office with a request, “could we heat it up a bit in the back, and maybe lower the altitude’? The heat was no problem, but the Alps made the cabin altitude a bit dicey! The doc’s next request was for a little more speed, as things were “starting to happen” in the tube, now known as the “Lockheed Pre-natal Clinic”! OK, “ Flight Engineer, Set 1010, Senior Chief.” A few minutes later, Senior Avery (remember him, the SS-3/Midwife?) calls up on the intercom and announces that we are about to have another entry for the “A Sheet”! At this point, LT Mike Kupfer, the copilot, and I were concentrating on shooting the ILS to Runway 25R at Frankfurt Rhein-Main. Somewhere out around the Outer Marker, we heard “it’s a girl”, and Jill Domogauer transformed the tube into the “Lockheed Delivery Room”!

Some claim that I then made the smoothest landing of my career, but then again, I thought they were all smooth! Now we can park this flying machine and get on with the festivities at Zeppelinheim! Little did we know!

As we were taxing to the Air Force side of Frankfurt Airport, we got the word from the back, “it’s not over yet, it’s twins! “ We stopped for a few minutes on the taxiway and Jill’s baby brother made his grand entrance! We blocked in at the USAF, 2nd Airevac Squadron’s Medevac line and were met by several ambulances and medical personnel. Since it was raining, cold, and windy, the ground personnel used a boarding stair truck to enter via the cockpit side escape hatch. Once everyone was secured in the back of the plane, the medical personnel took our patients off the normal way and we started to button up the plane for the night. Boy, I can taste that Wienerschnitzel and Bier now! Little did we know!

When we checked in with command post (remember, this is an Air Force base), there was a message for us to call Sig. I didn’t like the sound of that, but gave them a jingle anyway. “You need to ‘gas and go’ and bring the airplane back ASAP, we need it for a launch tomorrow”. Rats! I tried the old crew rest angle (remember, this is an Air Force base), but that didn’t work! Tired, excited at what we had just done, and disappointed, CAC-9 saddled up and made our way back to Sigonella. I don’t remember when we got back, but it was dark and tired out!

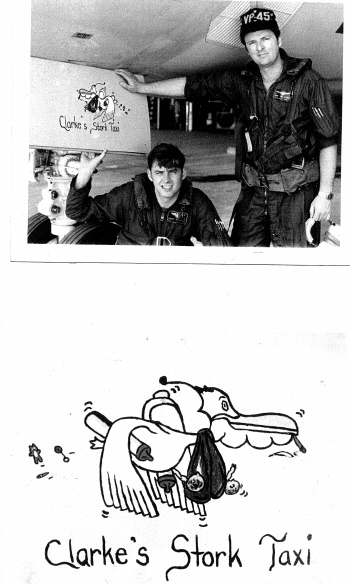

Turns out they didn’t need the bird after all, but as they say, “that’s the breaks of Naval Air.” While CAC-9 was crew resting, the Airframers were busy. When we got back to the squadron the next day, the nose gear doors sported a slightly modified Pelican with two babies instead of torpedoes and the title “Clarke’s Stork Taxi.” Several weeks later we were able to get the family together with the crew for a “photo op” with the crew and LN-48. Sig deployments aren’t all bad, are they?

Epilogue: The Domogauer twins now live in Myrtle Beach, SC and one is a police officer and the other a fireman. I retired from active duty as a Commander, after 24 years and flew P-3/C-130 as a contractor pilot for another 20 years supporting Navy flight test at Pax River. Of my over 14, 000 hours of flying, this was one of the most exciting/fulfilling flights, except maybe the time I had a fuel tank fire in a C-130, with a Super Hornet on the hose , aerial refueling …but that’s another story!

Flight Crew for “Medevac LN 48”

Pilot LCDR Tom Clarke

Copilot LT Mike Kupfer

Flt Eng AMCS Hampton

Radar/midwife AWCS Avery

Electrician AE2 Cloyd

Observer AW2 Hennesy

Flight Nurse LT Lisa Hiles

Corpsman HM2 Joni Kautsey

Doctor LCDR Soballe

© P-3 Orion Research Group / 1997 - 2017